When Demas Nwoko arrived at the Nigerian College of Arts, Science, and Technology (now Ahmadu Bello University) in Zaria in the 1950s, he encountered an art curriculum deeply rooted in European traditions, with little engagement with Nigeria’s own artistic heritage. Rather than rejecting modern influences outright, he sought to redefine them on his own terms. He joined forces with like-minded peers to challenge the rigid colonial framework, not by discarding modernism but by infusing it with indigenous Nigerian aesthetics. This philosophy led to his formation of the Art Society, alongside Uche Okeke, Simon Okeke, Bruce Onobrakpeya, and other visionary students. Amid the rising nationalist sentiment leading up to Nigeria’s independence in 1960, the group championed “Natural Synthesis,” a term coined by Uche Okeke to describe the fusion of contemporary artistic techniques with African traditions. Later known as the Zaria Rebels, their movement was not a rejection of modernism but rather a bold assertion that African artistic identity could evolve by blending the old with the new.

While many saw artistic modernism as a break from tradition, Nwoko saw it as an opportunity to broaden Nigerian art into new disciplines. He thought that combining indigenous aesthetics with modern inventions should not only influence painting and sculpture, but also architecture, theatre, and design. His approach to space and structure drew from traditional African forms while combining modern techniques to create works that were both functional and culturally meaningful. In the theatre, he redefined stage design by using African-inspired motifs and storytelling methodologies, ensuring that artistic expression remained directly connected to the realities of the people.

Unlike many of his peers, who focused primarily on painting and printmaking, Nwoko broadened the scope of artistic expression to include physical spaces and everyday experiences. His vision was holistic—art was not just something to be observed but something that could shape environments and daily life. For him, redefining artistic identity was not only about reclaiming visual narratives but also about reshaping how Nigerians engaged with art, integrating it into their surroundings rather than confining it to galleries or academic spaces.

His approach to architecture was especially groundbreaking. Rather than adhering to the dominance of Western-style architecture in Nigerian cities, he sought to blend African architectural methods with modernist principles. His structures incorporated natural materials, passive cooling techniques, and motifs influenced by indigenous cultural expressions. Nwoko's architectural philosophy was a direct response to the overwhelming European aesthetic in post-colonial Africa, demonstrating that African architecture could be both useful and particularly beautiful.

Despite their groundbreaking position, the Zaria Rebels had not sought to discard Western influences. Instead of eliminating them, they thought to recontextualise them in a way that benefited Nigerian culture. Nwoko and his friends did not consider modernism as fundamentally European; instead, they believed that African artists might include helpful features while remaining true to their own tradition. This was a paradigm change in thought, laying the groundwork for contemporary Nigerian art as it exists today.

The Zaria Rebels' influence stretched long beyond their student years. Their philosophy of Natural Synthesis helped define modern Nigerian art, inspiring generations of artists, designers, and architects. Nwoko, in particular, continued to push limits, distinguishing himself as not only an artist but also a cultural thinker whose ideas influenced everything from urban architecture to stage design. His work bridged the gap between past and present, demonstrating that African artistic traditions were not remnants of history, but evolving, flexible manifestations of modern identity.

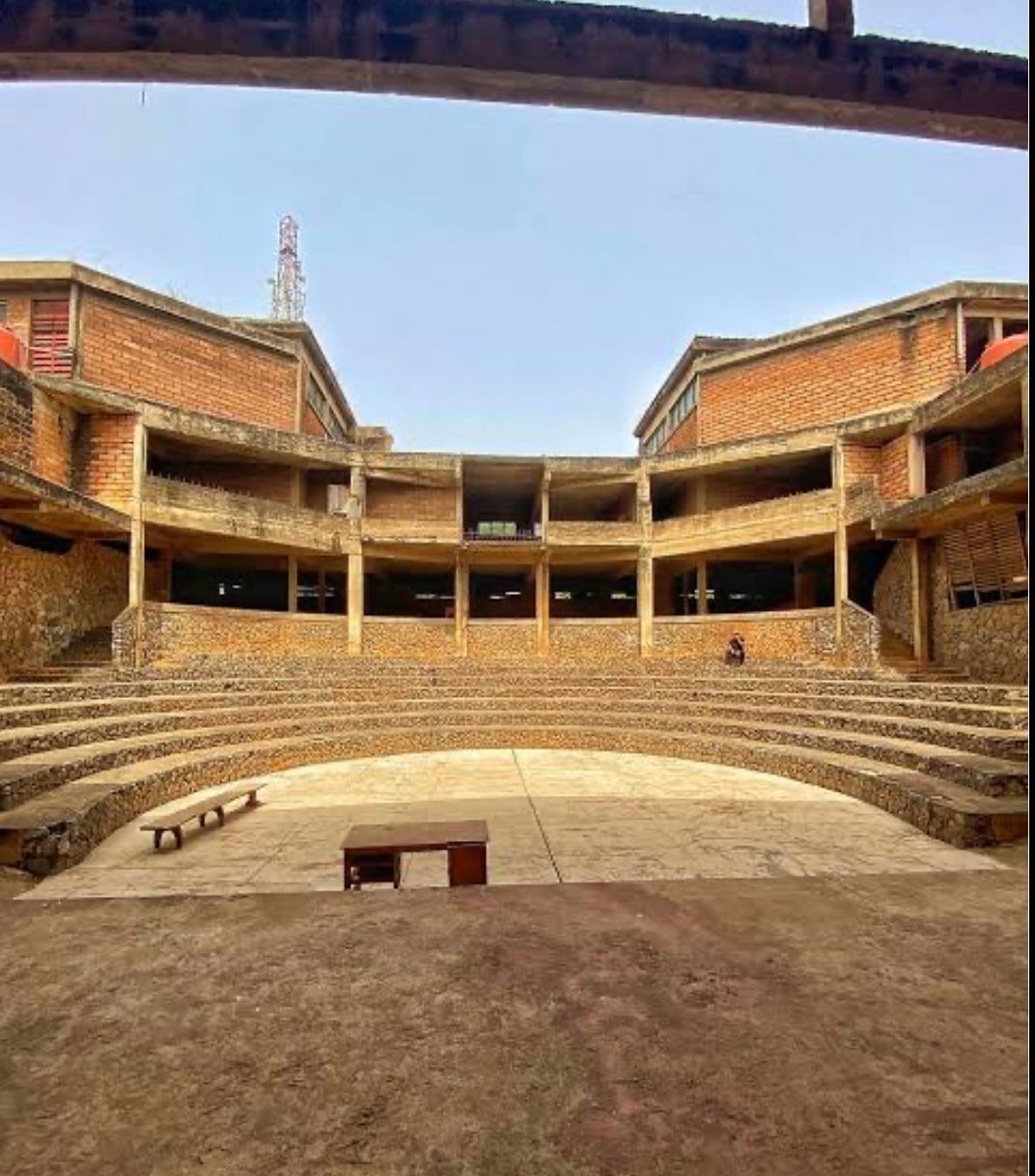

While other Zaria Art Society members were known largely for their paintings and sculptures, Nwoko's architectural contributions distinguished him within the movement. He did not consider art and function to be separate spheres; rather, he believed that architecture, like painting and sculpture, could be used to communicate cultural values. His projects, such as the Dominican Institute in Ibadan and the Cultural Centre in Benin, demonstrated his dedication to combining indigenous African architectural traditions with modernist ideals. These constructions were more than just functional spaces; they were artistic statements that showed African architecture could progress on its own terms, drawing from both tradition and creativity without simply imitating European models.

Nwoko's work in theatre and stage design, in addition to his architectural projects, displayed a thorough awareness of how space, culture, and performance intersect. His designs frequently used concepts from Indigenous performance traditions, ensuring that Nigerian storytelling remained visually and spatially authentic. At a time when many Nigerian theatres were erected in the European proscenium style, Nwoko experimented with stage structures that reflected indigenous performance settings, resulting in work that was both innovative and culturally entrenched.

The importance of Nwoko and the Zaria Rebels cannot be overemphasised. They provided an alternative to a system that had previously defined African art through a colonial lens, demonstrating that Nigerian artists could shape their own creative narratives. Their goal was not to completely reject Western creative standards, but to reimagine them from an African perspective. This was not an act of isolationism, but of self-affirmation, demonstrating that Nigerian culture was not only rich and complex, but also capable of shaping modern artistic expression on its own terms.

Despite their contributions, the evolution of Nigerian art did not stop with the Zaria Rebels. African artists today are still exploring the link between global influences and local traditions, looking for new methods to express their identities. However, Nwoko and his peers laid the groundwork for modern Nigerian artists to build on a tradition of thoughtful reinvention and cultural dialogue, rather than starting from scratch. The effort to define Nigerian art on its own terms continues, but thanks to the Zaria Rebels, it is guided by history and a rich artistic legacy.

In many ways, Demas Nwoko represents the core philosophy of the Zaria Art Society—a deep commitment to cultural authenticity, a reexamination of inherited artistic frameworks, and a belief in the strength of Nigerian artistic identity. His work, spanning painting, architecture, theater, and design, illustrates that shaping a modern artistic language is not about rejecting external influences but about weaving them into the richness of indigenous heritage. The art world often separates disciplines into neat categories, but Nwoko’s career transcends such boundaries. His legacy is not just in the structures he designed or the artworks he created but in the enduring idea that Nigerian art should be a dynamic reflection of its people, its traditions, and its evolving future.